Congregational Church of Brookfield (UCC)

October 14, 2014

“From Central America to Africa: Answering God's Call”

Good Morning. My name is Kevin Hoogenboom and I grew up in this church. I'm now 22 and just graduated from Lehigh University in Bethlehem, PA this past May. Today I'm thrilled to have been invited to share a little bit about how what I learned about doing God’s work growing up in this church has translated into my life away from home. What I’m talking about is service—service for those who are less fortunate. I’ll begin by sharing a quote Pastor Jen shared with me. It was written by Frederick Buechner and it reads: “The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.” It is this idea that is at the core of what I learned here and what I’ve continued while I’ve been away.

It began in 2007 when I went on my first Mission Trip to West Virginia with Senior Youth Fellowship. Seeing the poverty that we did on that trip and helping to improve the quality of life for people who were really struggling was a transformative experience. I enjoyed doing God’s work in this way. The following year we went to New Orleans; a year later, to upstate New York; and the year after that, to South Dakota. By the end of my high school career I’d been on four Mission Trips with this church—four impactful experiences.

So, when I headed to college I knew I wanted to continue this type of work. I got involved in an organization called Engineers Without Borders. A national nonprofit with hundreds of college and professional chapters across the country and about 15,000 volunteer members, the mission of Engineers Without Borders is to solve problems of development in low-income areas around the world. If you've heard of Doctors Without Borders, this is basically the engineering version of that. Each chapter has a project, ranging from the installation of clean water systems or proper sanitation systems, to the construction of new roads or bridges, to bringing electricity to a community for the first time. I had the pleasure of serving as President of Lehigh's chapter, a group of about 100 students, last year as a senior.

When I came to Lehigh, the chapter was finishing up one project in the Central American country of Honduras and ready to begin a new one in a community nearby. Our focus was clean drinking water--something you and I take for granted but something one billion people around the world lack. Why clean water? For those who don't have it, life is filled with chronic waterborne illness and great amounts of time and energy spent on gathering this essential resource. People waste time being sick or fetching water that they could spend at work or at school, so productivity is limited significantly. People are too weak or too busy dealing with something that's a complete non-issue for us, that they can't make enough money to support their family. Lack of clean water is a direct contributor to the vicious cycle of poverty and despair that people face all across the globe.

The first project at Lehigh was a water system for a town of about 1,000 people. Located in a rural, mountainous area, the community once had a distribution system that brought untreated water into town, but it was wiped out by a hurricane in 1999 and there were never any means to fix it. Sickness was rampant, especially among the children. Our chapter worked for 5 years to build a new network that delivered clean water to every household to eliminate this sickness, finishing up in 2011.

The new project was high in the mountains in a very isolated coffee farming community of about 300. These people have never had any sort of water system and have always just gathered what they could from streams and rainwater. This project is ongoing and, like the first, will bring clean water to every household in town.

Lehigh's newest project is a little different and just started last year. Located just South of Honduras in Nicaragua, it will bring clean water and sanitation systems to a campus that will house a high school, a computing center, and a medical services center for a rural region with about 6,000 people spread out over a large area.

Of course, these projects couldn't happen without students actually traveling to build them. I had the great opportunity to travel to Honduras once and Nicaragua twice and I'd like to share a bit about my experiences on these trips. I'll begin with Honduras. What a place. Such a beautiful country but so befallen by poverty, violence, and corruption. The housing situation was appalling. People literally live in huts made of sticks, straw, and mud. I'd seen stuff like that on TV but never in real life. And surrounding anywhere people live, there's about a 500 foot radius of garbage just strewn about. Trash collection in Honduras is limited to the cities. Anywhere else, people just toss their garbage out the back door. Seeing this was probably the most unexpected thing for me. There was trash everywhere. In the rural areas where we worked, interior plumbing is nonexistent and there is no such thing as a bathroom in a house. People use the most rudimentary of outhouses, many of which leech right into the streams from which everyone gathers water. Most places have electricity--the town our newer project is in just got it about 5 years ago--but it goes out whenever there is any rain or wind, and at other random times. Emergency services are absent. There is no 911 and most of the police are corrupt and involved in the drug trade. But a lot of good and decent people live in Honduras, and it was painful to see how hard everyday life is for them.

Take Rolando. Like everyone else, he's a coffee farmer, working hard every day for minimal pay. He lives in a tiny hut with his wife and 5 year old twin daughters, as well at least 10 chickens. There are tons of chickens in Honduras. As soon as I met this man I felt God's presence. He was so thankful to have us there and so willing to do whatever he could to help the project succeed. He took us all over, literally thrashing through the jungle with a machete to show us where everything we needed to survey was. He had all seven of us into his home on the first day we met and served us freshly brewed coffee. He gave us three enormous bundles of bananas--like 200 of them--from his banana trees. He even hand-drew a map of the town for us with a level of detail far beyond our expectations. I never heard Rolando complain and he just never stopped working. I can't describe enough how crucial his help was, and I know God was there to connect us.

And then there was Mateo, the school teacher in town. From day one I could tell he was special. Mateo is more educated than most in Honduras and could have found work in more accessible places, but he had visited this village two years prior, seen how much it was struggling, and knew he wanted to help. As a result he has a commute in excess of 3 hours one-way and usually only is able to go home on the weekends. He also has been an asset for Lehigh, standing by Rolando's side and helping to organize the community. He doesn't even live there, yet he has invested so deeply in the people. You see a community living in such poverty, but you meet such extraordinary people--people who are pouring their hearts into making things better--and you can't help but think God is watching over.

Most of our time in Honduras was spent surveying, taking water and soil samples, and conducting other project tasks, but some of the most lasting experiences were in the evenings when the children in the neighborhood we stayed would come outside and flock to our porch. The majority of our group spoke little Spanish, but we had no trouble having a ball with these kids. We played sports, read stories to them, and just hung out. And most of them had some seriously rough situations. 10 year old Yolanda lost her teenage brother to gang violence. 3 year old Mimo lived in a household stricken by alcohol abuse. 7 year old Javier was homeless. And of course, none of these children had clean drinking water or proper sanitation or so many of the other amenities I never had to worry about as a child. Despite all that, Yolanda, Javier, Mimo, and all the others were full of smiles, full of laughter, and full of love. This made our work all the more meaningful.

As Honduras's Central American neighbor, Nicaragua has a lot of the same issues of poverty. The country as a whole is safer and in somewhat better shape economically, but we worked in an area with particularly intense rural poverty. Most of the villages in this region are so isolated that there's no electricity and not even any cars. People actually travel by horse or by oxen-driven carriages. During the dry season, they walk miles just to find water, let alone safe drinking water. The only places to work are on farms. I remember speaking to one woman, who lived in a run-down mud-hut with a thatched roof, and she said she spent 5 to 10 hours collecting water each week. Can you imagine?

We visited village after village where the living conditions were just deplorable. But the woman who took us around, Antonia, was truly amazing. Antonia runs the operations of a major nonprofit in the area that installs water filters, properly-ventilated stoves, and other types of health improvement devices in rural homes. She's the only full-time staff member and is in charge of coordinating volunteer efforts in over 30 rural communities. Antonia has single-handedly led to the improvement of hundreds, if not thousands, of lives. She also was a tremendous help to our efforts, offering the most insightful advice and spending many hours each day just being the guide we needed. I have no doubt that God is working through Antonia.

It's no exaggeration to say my trips to Honduras and Nicaragua were life-changing experiences. Being able to do God's work in these places so very different from my home was incredible. But I did go to one more place, and although it wasn't for Engineers Without Borders, it was in the same realm. This past March I traveled to Kenya, located on the coast of eastern Africa along the Equator, as part of a Social Entrepreneurship class aimed at helping businesses grow. My project in particular was to help a clean drinking water operation get off the ground. Kenya was a completely different and equally life-changing experience. The poverty was on another level. It's hard to put into words what I saw, but there are just a lot of very poor people over there. On the whole, people in Honduras and Nicaragua don't have to worry about having enough food to eat. This is a legitimate concern for a sizeable portion of the Kenyan population. Kenya has a major problem with homeless people, especially children. There are tens of thousands of what they call "street boys," boys who leave home and go to the streets because their parents cannot afford to feed them. Like Central America, the rural areas have more extreme poverty. People live in very shoddy huts, packing more people than I could believe into tiny, dark spaces. A lot of rural areas don't have electricity, and the vast majority lack access to clean water or proper sanitation.

Kenya is a beautiful country. It's high in elevation and has spectacular mountains. Of course it also has the savannah, complete with all of the exotic animals we see in National Geographic. The Lion King was based off of Kenya's Rift Valley. I was within feet of lions, cheetahs, giraffes, elephants, zebra--the whole gamut. Out on the savannah, people are few and far between, but we did see one village that perhaps was the most shocking thing I've seen on any of my trips. It was a nomadic tribe that lives about 7 hours from the nearest town, all alone, with no electricity, no agriculture, almost no trees for fuel, certainly no vehicles, and absolutely no means of work. All they have are livestock, kept in a small, unsanitary area in the middle of all the houses, which were arranged in a circle. The men go out on hunts during the day while the women walk miles to gather food, water, and fuel. It was surreal to see people living like this. Yet, they were very proud of their heritage and their way of life.

Most of my time in Kenya was spent in more urban environments. We worked with a man named Josephat, who runs a business that makes hand-made fishing ties for clients in places like the US. We worked with Paul, who sells milk out of a van that he must take on a three hour round-trip every day just to collect a few dozen bottles. We worked with a girls soccer team that gives girls a positive environment, most of whom have left home because there wasn't enough food to eat. And we worked with a water business that aims to bring clean drinking water to communities. With each business, it felt like we were turning the clock back 100 years. Kenya is just so far behind in so many areas.

I'll close my discussion of Kenya by sharing the most moving experience I had. On one afternoon my group went to visit a market where many of the street boys I mentioned before hang out, waiting each day for the scraps of food that vendors throw away. It was hard to see. There were so many of them. Almost all were on drugs. They sniff glue--a cheap and readily accessible substance--as a way of coping with the pain of daily life. At one point I went to greet one of the boys, probably about age 12. I don't even remember his name, but as soon as I went to shake his hand he just started to hug me, and he didn't let go. I hugged him back. In that moment I knew God was there, and I'll never forget it.

In closing, doing this work in three different countries has been a unique opportunity but also quite the learning experience, so I wanted to share a few things I learned. First, I learned that making personal connections and building relationships is the absolute most important part of doing development work. The engineering may be perfect or the plan may look just right, but the effort will never succeed in the long term if the primary focus isn't people. Second, development work takes time and it takes patience. Making those personal connections and making sure things are done right is a process, not an event. And this type of work is a two-sided effort, requiring commitment and trust from both sides - it takes time to create that. You have to control that desire to get out and build something right away, because long term solutions require long term efforts. Third, you have to free yourself from judgment and see the value in each person you are helping. Everyone is fighting an uphill battle. We're all human and we're all connected. Everyone has something to teach, and everyone has something to learn. Finally, God is always with you. Sometimes when I was deep in the jungle of Honduras or halfway across the globe on a Kenyan street I felt like I was so removed from everything in my life that maybe God wasn't there either. But each time I was reminded, by a boy I'd never met hugging me at random or by a man with hardly enough food for himself giving it away to me, that God is always with me. And that was enough to keep me going.

Engineers Without Borders

Today, more than two billion people lack access to the most basic things, such as clean drinking water, adequate sanitation, reliable passage to local markets and more. Engineers Without Borders USA (EWB-USA) is engineering change in 39 countries around the world to change this reality -- one well at a time, one bridge at a time, one community at a time.

Our mission: EWB-USA is a nonprofit humanitarian organization established to support community-driven development programs worldwide through partnerships that design and implement sustainable engineering projects, while creating transformative experiences that enrich global perspectives and create responsible leaders.

Our vision: EWB-USA's vision is a world in which the communities we serve have the capacity to sustainably meet their basic human needs.

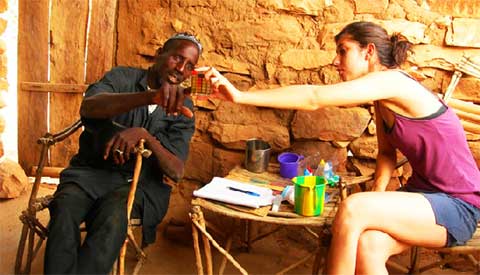

An EWB-USA member from the EWB-USA University of Arizona Chapter shows a community member in Mandoli, Mali, how to examine and assess the quality of water with a water test.

This page was last updated on

11/05/2014 12:32 PM.

Please send any feedback, updates, corrections, or new content to

.